“Soccer and image rights” written by our partner Raquel Flanzbaum for MARCASUR

We share with you the article “Soccer and image rights: a photograph is worth a thousand words”, written by our partner Raquel Flanzbaum and published by MARCASUR. We encourage you to read it!

Soccer and image rights: a photograph is worth a thousand words

The protection of the image of the human person is the subject of both Industrial Property and Copyright Law. And in Argentina the relatively new Civil and Commercial Code also addresses this issue.

These past days, the death of Diego Maradona has brought to memory many aspects of his life, including his having registered as a trademark his name, his surname and his nicknames, as well as the use of his image for advertising many products. It may therefore also be appropriate to recall now another great Argentine soccer star, Alfredo Di Stéfano, who in the early 1960s starred in an advertising campaign that at the time was considered extremely daring.

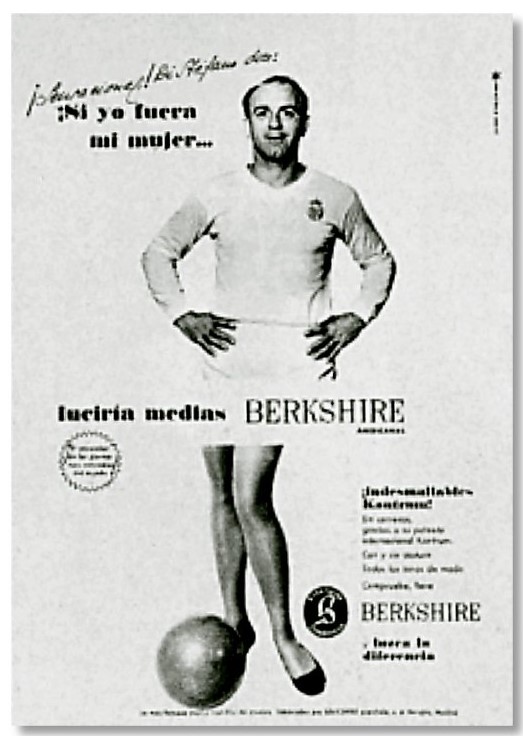

It was an advertisement for women’s stockings, which depicted the great player saying “If I were my wife… I would wear Berkshire stockings,” with his full-length photograph, with him from the waist up in the usual attire and appearance of a very masculine soccer player, and from the waist down with a woman’s suggestive legs, elegantly dressed in the stockings in question and, if anything else was needed, high-heeled shoes.

What is more, the campaign ran both graphically and on television. It was December 1962, and, needless to say, it was an immediate sensation.

Santiago Bernabéu, the president of Real Madrid, the club where Di Stéfano played, was furious. (To add a colorful note, when he first arrived in Spain Di Stéfano very nearly became a Barcelona player.) If Di Stéfano was one of the two great stars of world soccer (at the time the other star was Pelé), Bernabéu did not lag far behind: after a great career as the scorer of Real Madrid in the 1920s, first as an officer and later as president he had transformed the club into one of the most important institutions in Europe. (Another colorful note: for a year Bernabéu played for Atlético Madrid, Real’s sworn “enemy.”) This was a true clash of giants.

Bernabéu ordered Di Stéfano to stop the advertising, which the player refused to do. He had collected 150,000 pesetas (at that time the price of an apartment in Madrid ranged from 300,000 to 500,000 pesetas), and in the end it was Bernabéu who returned the amount the player had received from Berkshire. (Another version has it that it was Di Stéfano who returned the money.)

Today being a transgressor is practically routine. But in the early ’60s, in Spain, things were quite different: it was the Franco era, with other ethics and aesthetics, much closer to the Spanish and European post-war period than to the great changes that were about to come.

But Don Alfredo was not only a pioneer in the management of his image, but roguish, lighthearted and with great commercial cunning, he knew how to overcome the rigid boundaries of the roles assigned to the genders and was not afraid to star in a different, daring and striking advertisement.

Sixty years ago Alfredo Di Stéfano, the great soccer player, was also the great pioneer.