Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property: The creation dilemma under current legislation in Argentina.

“If we give the machine a program that results in it doing something interesting that we had not anticipated, I would be inclined to say that the machine has caused something, rather than claiming that its behavior was implicit in the program, and therefore that originality lies entirely in us.”

Alan Turing (1912 -1954)

Much has been said about the emergence of new technologies. We cannot avoid the question that arises from them: Who owns the rights derived from a creation using Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

As we know, in every creation what has been protected is the innovation of those human beings who create a product and/or a service whether artistic, cultural, literary, technological, etc. But What happens when they are not generated through human intervention?

Technology of the future that is already part of the present

AI is increasingly present in everyday life. We interact with AI systems to carry out everyday activities such as listening to music, watching series, finding a route, or buying an item online. Many tasks that were performed by humans in the past have been replaced by algorithms in recent decades and have now been incorporating this technology extensively.

There is no internationally accepted definition, but we could say, in principle, that AI is the ability of a machine to present the same capabilities as human beings, such as reasoning, learning, creativity, and the ability to plan.

Within it, we can find a subset where computers learn from data and improve with experience without being explicitly programmed (Machine learning), a term proposed by Arthur Samuel in 1959 and which in 1997 Tom Mitchell was

responsible for giving an oriented definition. to the most up-to-date computational engineering, this AI technology is the most used now.

The creator is the one who creates

In our legislation, Article 17 of the Constitution of the Argentine Nation establishes that “Every author or inventor is the exclusive owner of his work, invention or discovery, for the term granted to him by law.” Likewise, when the term “author” is used in our intellectual property legal regime (Law 11,723), it refers to a human person.

This statement is also supported by norms such as Article. 4 of said Law, which establishes that “The owners of the intellectual property right are: a) The author of the work; b) His heirs or successors in title; Article. 5, which declares that “Intellectual property over their works corresponds to the authors during their life”, among others. If it refers to the author’s heirs, to the life of the author, to his death, it is because it assumes that the author is a human person whose life cycle is real.

Therefore, we find ourselves with the debate today about the authorship of a work (any) created by AI since it cannot yet be determined with certainty who will be the owners and subsequent benefactors of the royalties whose work obtains.

Creation (and creativity) about a non-human. Some examples:

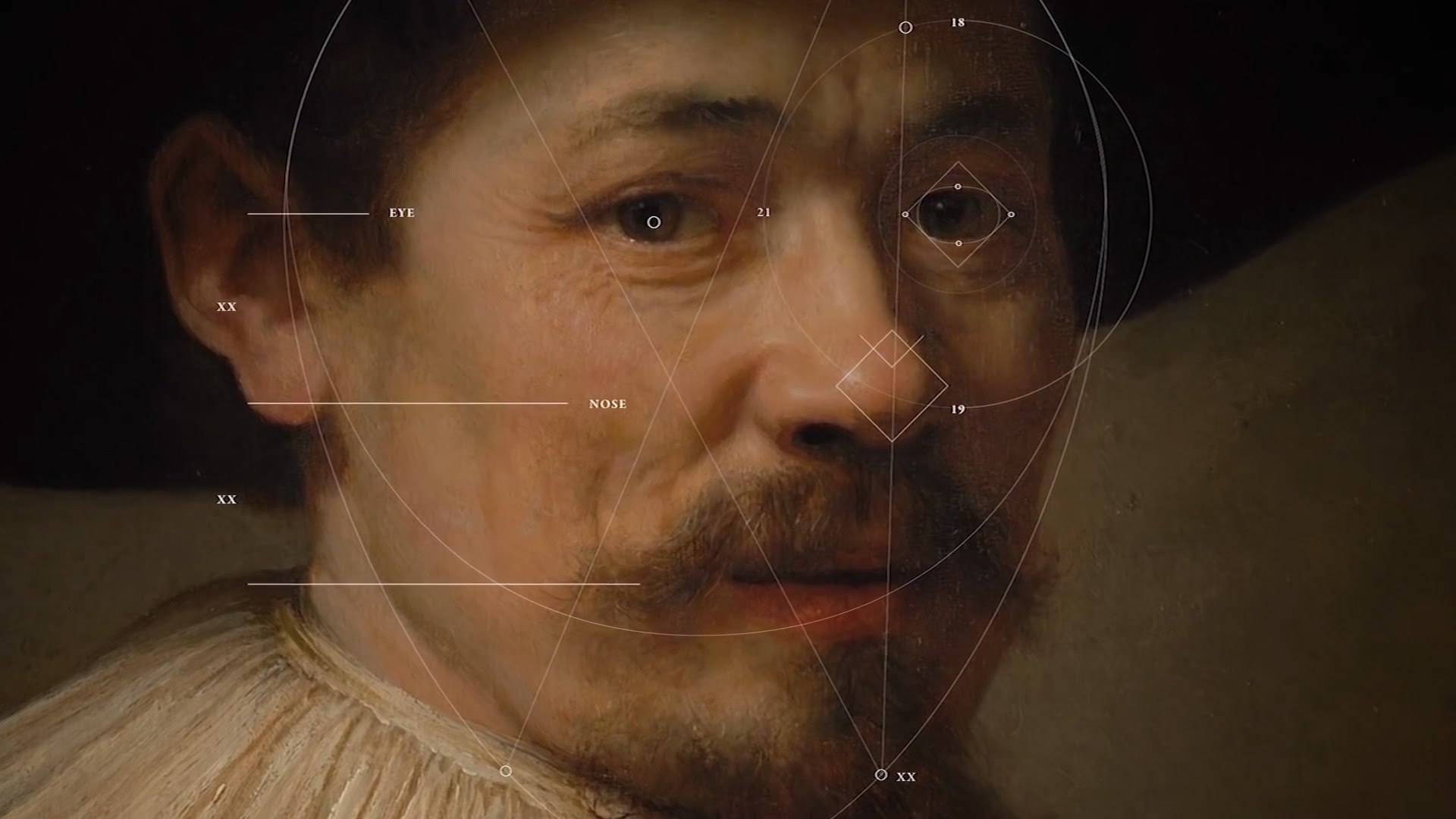

THE NEXT REMBRANDT

In the field of painting, ´´The Next Rembrandt´´ project shows how a new portrait of the renowned painter has been created using the analytics of an AI program and 3D printing. In this project, a printer with these characteristics was used since the paintings are not only 2D but have a distinguishable three-dimensionality that comes from the brushstrokes and layers of paint of a real painting. This difference was key to its development because it served to study and scan, first, all of Rembrandt’s works, and later, analyze the patterns used by said artist. This is how, by imitating these patterns, a painting with its characteristics was perfectly replicated. The result obtained has been very controversial since many consider it a copy instead of an original work.

In the world of music, we find the EMI program (Experiments of Musical Intelligence), created by David Cope in 1981, which was born from the idea of helping a composer when the latter suffers a mental block and is unable to continue composing. This program recommends notes in such a way that it is the one who continues with the melody in case its main author runs out of inspiration. In this way, David defends that “the music that algorithms compose is as much ours as the music created by the greatest of our human inspirations.”

Both examples cited above correspond today to what we know as “Generative Art”. This art represents those algorithms that create “works” on their own without the need for any type of human intervention. This term was established by Margaret Ann Boden who also referred to “Evolutionary Art” regarding those programs that create “works” and whose results are unpredictable.

It is very difficult to attribute the creation

So, if copyright arises by originality, some of the “creative” products generated by AI, which, from a certain point of view would be considered original works, could be left devoid of legal protection precisely because human participation is minimal or none. And also because copyright belongs to the author, that is, a human or natural person who creates an original work, and the current regulations do not contemplate situations to resolve a possible “ownership of the machines.”

The ability of robots to create or invent autonomously is shaking some of the pillars on which the general Intellectual Property rules are based, which only protect creations developed by humans (Andrés Guadamuz Artificial Intelligence and Copyright, WIPO Magazine, Oct. 2017)

In this situation, different types of actions are already being undertaken. The European Union, for example, is considering new requirements that would be legally binding on AI developers, in a bid to ensure that modern technology is developed and used ethically.

However, it is intended to establish at this point that any intellectual creation that can be developed in the current state of the art always requires the participation of the creativity of the human being, whether in the form of a natural person or a legal entity through its members. Consequently, to think that an intellectual creation can be developed by a computer or any other type of machine, without the direct or indirect intervention of the human being is to date unthinkable, both in our country and in other parts of the world.

The evolution of intellectual property rights is much faster than those of real property

At the beginning of 2020, the Tencent company decided to take Shanghai Yingxun Technology Company to the Shenzhen courts for violation of its copyright. The case arose because the defendant had taken a journalistic article generated autonomously by the AI system “Dreamwriter” and had uploaded it to its website. Given these facts, the Chinese court decided to condemn Shanghai Yingxun Technology Company for damages derived from the violation of Tencent’s copyright on the information generated by its AI system. The interesting thing about all this is that the court did not go into detail about the problem of authorship, but rather based its decision on the reasonable, logical, and original character of the work generated by the AI, these characters being sufficient to justify the existence of intellectual property rights over the works.

DABUS is an artificial neural network created to generate inventions. In 2019, it created two products. On one hand, a container for food, and, on the other hand, a fractal light to alert in emergencies. The interesting thing is that its creator decided to patent both inventions but with a peculiarity: instead of presenting himself as the inventor, he decided to challenge various patent offices on the planet and request a patent application in the name of the AI, who, in his opinion, it was the true inventor of the products. He had filed several applications at patent offices in the United Kingdom, the European Union, the United States of America, South Africa, and Australia, among other countries, but the patent applications were denied, all for the same reason: lack of authorship.

None of the entities denied the patentability of the invention itself, however, the examiners of said patent offices where the creation was denied, argued, on the one hand, that the AI did not have legal status and therefore could not be the owner of intellectual property rights, and on the other, that when their rules speak about of the need for an author, they do so referring to a human author. If the creator of DABUS had presented himself as the original inventor, he probably would have obtained the patents. However, hiding the relevance of AI in the creative process means hiding its creative potential and not being able to demonstrate its true value.

Anyway, DABUS’s fortunes changed at the end of July 2021 when the South African Patent Office decided to grant the requested patent applications, becoming the first country to grant a patent to an AI-based inventor. In turn, in Australia, the Patent Office originally rejected the submitted patent applications, however, the issue was submitted to the Federal Court of Australia, which decided to grant the requested patents and made it clear that “an inventor can be an artificial intelligence system.”

If each thing analyzed at this point is taken into account, there is a need for Intellectual Property Organizations to rethink certain concepts to accommodate the growing technological development and, why not, algorithmic work or the protection of some products. of AI. It is imperative to rethink some traditional figures and concepts, since new creations are being generated that could be devoid of legal protection because the law moves at a different speed.

Final thought

Having read the data shared by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) from 2019 to the present, it is undeniable that these results reflect the rapid growth of innovation in AI. This accelerated development poses a series of political challenges to national and international governments and regulatory entities that must take note of what is currently happening as soon as possible.

For further information please contact abravoalzamendi@ojambf.com